By Maureen Nichols, South Southwest ATTC director

Much of the work by the Addiction Technology Transfer Center network and their partners in behavioral health care systems focuses on making changes that improve the lives and health of communities, families, and individuals.

Examples include providing intensive training, feedback and coaching to counselors working in substance use treatment programs in a specific evidence-based practice, such as Motivational Interviewing (MI), or supporting a primary care clinic in a change process to implement Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral (SBIRT) for substance use for all of their patients. Many times, change projects run up against unplanned system barriers that blunt positive outcomes: high turnover in staff results in loss of counselors with MI training and experience, policies and procedures at the primary clinic impede implementation of SBIRT.

As a tool for planning for system changes projects, the South Southwest ATTC has incorporated a systems research framework developed by John J. Kineman, PhD, that we have found to be a useful tool for understanding complex systems: the PAR Holon Framework[1] .

PAR Holon Framework

The framework applies broadly to systems, and is derived from two sources, relational biology and Participatory Action Research (PAR). The framework was first introduced as a tool for discussing approaches to system change during a Region 5, 6, and 7 SAMHSA and Regional ATTC project focused on aligned workforce development and career ladders for Peer Recovery Support Specialists and Community Health Workers in 2018.

We have since gone on to use the framework as a way of intentionally organizing our thoughts around system change strategies in a variety of contexts.

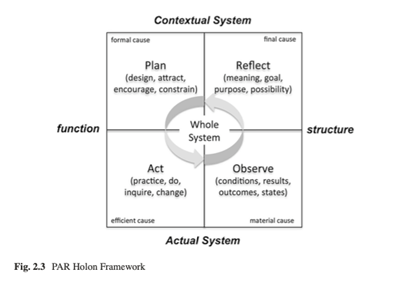

The framework visualizes four components of a complex system, represented by four quadrants. The first two, on the bottom left and bottom right, represent actions taken in a system and resulting outcomes. They are similar to the structure of a traditional logic model utilized in implementation of a new project, in which we envision a series of actions leading to a series of outputs and outcomes. They also correspond to the Act and Observe phases of participatory action research.

The top right quadrant of the framework represents goals,

purpose, and meaning that individuals within the system bring to the

functioning of the system itself. The upper left quadrant reflects the

permissions and restrictions every system works within – what can and cannot be

done. These quadrants correspond to the

Plan and Reflect phases of participatory action research. Each quadrant interacts

and impacts the other simultaneously within a complex system.

Additionally, complex systems have many subsets, or layers, that reflect these same four quadrants.

For example, in a health care system there is an individual layer, between a patient and a doctor, or an individual seeking support in recovery and a peer recovery specialist. At this level, there are actions that take place, (consultations, tests, planning, referrals, for example) and outcomes of those actions for the individual that can be measured (physical, mental and quality of life).

Each of the pair of individuals brings their own values and beliefs to their interaction in the system and works within a set of permissions and restrictions (affordability, insurance rules, ethical guidelines, etc.) that underlie the system. Another layer in a health care system is training and education, where providers take action to obtain training and education, which results in workforce level outcomes, professions have a set of established values and ethics, and boards existing to set and monitor licensures and certifications.

At a service provider organizational level, there are program designs and steps to implementation, outputs, and outcomes that can be measured at an organizational level, organizational mission and visions statements, and rules and regulations that organizations must adhere to in order to remain in good standing and stay financially viable.

Additional layers can be considered, around funding and regulation, community, family etc.

Using this multilayered framework to diagram components of a system allows change makers to discuss the best intentional approach to their work. Should we begin in the lower right quadrant, designing out change strategy based on the existing data? Do we seek to influence people beliefs and values around the system change, which might then impact their actions and permissions and restrictions? Do we provide additional funding for our change activities, which provides people permission to take actions to support the change goals. At what levels of the system will our change initiative have the most impact? Where are our change efforts pushing up against existing components of the system and experiencing resistance? What if the outcomes we seek are for people who are minimally engaged with the system, if at all?

Visualizing the complex interactions using this framework helps us prepare and respond to change efforts in systems.

[1] Kineman,

J. [Chapter 2]. (2016) P. B. Systems research framework. In M. C. Edson,

P. Buckle Henning, & S Sankaran (Eds.), A guide to systems research

philosophy, processes and practice. (pp. 21-58). Singapore: Springer

Publications.

About the author

Maureen Nichols is Director of the South Southwest Addiction Technology Transfer Center

(SSWATTC), at the Addiction Research Institute in the Steve Hicks School of

Social Work at the University of Texas Austin. She has thirty years of

experience in substance use program development and evaluation at the state and

community level. Her professional areas of focus include systems change and

quality improvement, technology transfer, and mental health and substance use

recovery.